My Evangeline

White Bread and Mardi Gras Queens in the Deep South

- Acadie exists in the real and the imaginary defeats it.

- —Gérald LeBlanc

I grew up under the sign of Evangeline. Not the epic poem of the Acadian diaspora by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow—I was born too late to be required to memorize passages from it, as were generations of school children after the melodramatic poem became a nineteenth-century bestseller. Evangeline propelled Longfellow into international celebrity and drove countless children to distraction. In case you weren’t one of those children, Longfellow’s narrative poem tells the tragedy of Evangeline and Gabriel, the legendary star-crossed lovers who were separated during the 1755 British expulsion of the French Acadians from Acadie, now Nova Scotia. Longfellow’s dactylic hexameters were not my generation’s bugbear.

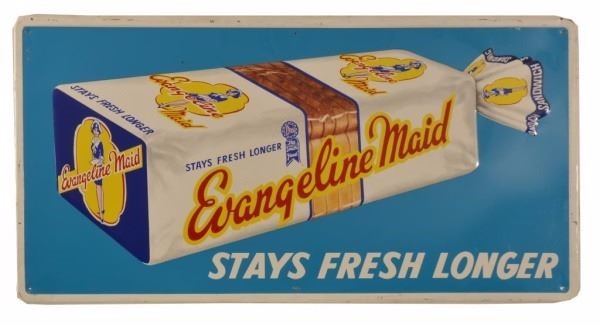

Instead, I grew up with Evangeline Maid Bread, the Cajun version of Wonder Bread. Bland and fibre-less, the spongy loaves were like little ready-made Claes Oldenburg sculptures. The bread’s soft angel-food texture meant that a loaf could be easily dented by a can accidentally placed on top of it in the grocery bag. I remember my mother rescuing more than one loaf from the cashier’s careless hands and carrying it unbagged to the car, keeping Evangeline Maid’s pristine geometry intact.

In my hometown of Lafayette, the hub of Cajun country in south-central Louisiana, Evangeline’s name also graced other kinds of businesses (an optical shop, an apartment complex, a steakhouse, a horse-racing track) and at least one public work (the Evangeline Thruway). Like Santa Claus at Christmastime, she was everywhere, and unmoored from her tragic legend, she was for me a symbol of home, like the moss hanging from live oaks.

Evangeline Maid Bread is my madeleine: although my taste in bread has changed since the 1960s, I remember the bread of my childhood fondly as an emblem of comfort and stability. My mother never bought any other kind of bread, even when it was on sale, and thus I, too, was brand loyal to Evangeline. Every time my mother drove down a certain street, I’d roll down my window in anticipation of the yeasty aroma that flooded the air as we passed by the Evangeline Maid Bakery with its novelty three-dimensional billboard featuring a rotating loaf of bread. You couldn’t invent a more perfect artefact of Cajun Americana.

Photo by Edward N. Leger

For a long time, I didn’t know who or what “Evangeline Maid” was. Her name and French maid’s uniform on the plastic bag suggested that she cleaned houses. As a child, I wasn’t sure why a housemaid would be associated with bread, but I registered the incongruity as just another aspect of home with its mysteries and absurdities.

Was there a moment when I realized that not everyone in the country ate Evangeline Maid Bread? The awareness that I was born into a unique culture (in which some older Cajun folk still referred to people outside their close-knit society a bit derisively as “les Américains”) was a series of small epiphanies.

Growing up in 1960s Lafayette, I was surrounded by the social and cultural rituals common to the large extended family of the Cajun community in south-central Louisiana, my paternal homeland since the eighteenth century. Food was, and is, a Cajun idée fixe, and even my waspish mother learned to make provincial comfort food like gumbo and crawfish étouffée. She drew the line at boudin (a spicy pork liver sausage), “coosh-coosh” (a gruel of corn meal and cracklins—the Cajun interpretation of North African cous-cous), and hog’s head cheese (no explanation needed). These pungent, artery-clogging Cajun staples were not fit for her consumption, so I relished them with my father after our fishing trips in the swamps of the Atchafalaya Basin.

Cajun food staples such as shrimp, rice, frogs, watermelon, alligators, jambalaya, crawfish, and gumbo provided the basis for a myriad of festivals that dotted the map of south Louisiana, as well as an excuse for Cajuns to cut loose and “laissez les bons temps rouler.” And the big daddy of festivals in Cajun country was Mardi Gras in Lafayette.

Racial segregation in my hometown during the 1960s necessitated two Mardi Gras parades: one in the morning for whites and one in the afternoon for blacks. The white parade (the more staid and “white bread” of the two) was sponsored by the socially prestigious Krewe of Gabriel (a “krewe” being a private club that organizes and funds its own parade). Every year at a pre-Mardi Gras ceremony of uppity glitz, this krewe crowned a new Queen Evangeline and King Gabriel and appointed their entourage of attendants and pages. King Gabriel was elected from the elite group of successful middle-aged business entrepreneurs of the town, and his Queen Evangeline was chosen from the ranks of nubile debutantes, whose rows of prim portraits in tiaras and white gowns justified the society pages of the Daily Advertiser.

Thus was Evangeline, the tragic peasant maiden, transformed without the slightest irony into kitschy Renaissance royalty, an overt icon of wealth and power in the little social pond of Lafayette and a covert symbol of Jim Crow racial supremacy. The Krewe of Gabriel parade through downtown Lafayette was an interminable procession of these sequinned and feathered social elite riding gaudy, tractor-drawn floats. In a demonstration of tacky noblesse-oblige, masked members of Evangeline and Gabriel’s court tossed plastic beads and “dubloons” to their subjects pleading with outstretched arms for a trinket.

Such displays were part of the traditional fabric of life. So was Cajun French, the first language of my father and his nine brothers and sisters. When the Acadians voyaged from France to settle in Nova Scotia during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, their language, effectively cut off from the mother country, retained some now-antiquated expressions and over time took its own evolutionary path. I never learned Cajun French because it wasn’t spoken by my parents, my mother being of Anglo-Germanic stock from the western prairies of Louisiana. But frequent visits to friends and family were the social glue of Cajun life, and I was exposed often to Cajun French when I accompanied my father to call on his myriad of friends and family. I believed then that he was content to keep French as a code language in order to talk about me in my presence. I could hear my name periodically surface above the lilting babble, the only transparent word in an opaque language that I could no longer learn by osmosis.

Some Cajun words in my vocabulary were, as I found out later, considered by “proper Parisian French” people to be vulgar interjections. These obscenities were no doubt prohibited in mixed company by the Acadians. However, over the two-and-a-half centuries following Le Grand Dérangement, the taboo words had become so diluted that innocent children could spout them with impunity, unfearful of adult censure because nobody either knew or cared what the words had originally meant. My friends and I regularly called each other a “couillon,” which to us was a mildly teasing word that meant something like “idiot.” But I was awakened to its rudeness to those in the know when a student from Marseilles touring with his high school chorus stayed for a few days with my family, who had obliged me by requesting a boy. I invited my friend Colette to meet Marc, and at one point I, in all innocence, called her a “couillon.” The boy’s ears turned red as he gently admonished me not to use such language. I don’t think that the boy had quite enough mastery of English to tell us what it meant, and if he had, he probably would have spared us out of politeness. Years later, I looked into its etymological roots and discovered that my friends and I had been calling each other “testicles.”

In short, the Cajun side of my life was associated with traditional food and music, joking chatter, and a broad social network engaging in frequent social grooming. Sometimes it felt as though I were living on an island whose culture was becoming increasingly diluted by the bridges connecting us to that amorphous “mainstream,” which I associated with national television programming and commercials, superhighways, my parents’ contemporary-style house, and most books. When I was six, the ABC network was finally piped into Lafayette, just in time for my family to witness the American television debut of the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show. That and the soap opera that my mother was addicted to, As the World Turns, as well as the quatrains of Omar Khayam that I used to memorize as a budding adolescent poet, were filed in a different part of my brain from the local culture.

Another, and more distressing, factor in my realization of the uniqueness of the Cajun culture arose from the oil-and-water marriage of my parents: my father was as pure a Cajun as you could get, and my mother was of German/Scotch-Irish descent. There could not have been a more unlikely pairing, and the chasm between the two made me hyper-aware of cultural difference. I secretly nicknamed my Cajun relatives the “freewheelers” and my maternal relatives the “teetotallers” and felt estranged from both, constantly looking over the shoulders of each culture, not feeling that I belonged to either.

Behind the wall of her taciturn nature, my mother was nurturing and caring in her own practical way. She sewed countless dresses for me, and I relished driving with her to fabric stores to pore over endless patterns from Simplicity and Vogue catalogues and to select exactly the right colourful print from among hundreds of bolts. I enjoyed mounting the spool of thread atop her old Necchi sewing machine and winding the thread along its complicated twists and turns, a task she dreaded. My mother also planned family vacations to Colorado that broadened possibilities for life: mountains instead of flat horizons, alpine lakes instead of swamps. If childhood with her was often rocky, I felt a closeness and allegiance to her that arose from her devotion to me, her intellectual curiosity, and her rich, quirky language.

She may have married a Cajun to counterbalance her own reserved and carefully controlled nature. But transplanted into the midst of the freewheelers, my mother, with her preternaturally proper enunciation of English and rigid bearing, must have felt like a salt-water flounder tossed into a brackish bayou. A product of 1950s consumer ads, she represented everything modern, efficient, stainless steel. The relaxed interpersonal boundaries of her in-laws brought out in her a snobbishly pretentious streak. When I was twelve, I prodded my parents until they invited the Cajun parents of my next-door pal Geraldine to our house for dinner. I desperately wanted my parents to be more sociable, like Geraldine’s parents, who every Saturday evening had a raucous and jovial gathering of friends over to play bourré, a popular local card game. Before the Sonniers arrived, my mother had her hair done in her usual helmet style. She set as formal a table as she could muster, with tablecloth and cloth napkins, and put on an LP of classical “dinner music.” I had never before seen her put on such a production, not even for Christmas or Thanksgiving.

When the Sonniers arrived, my mother’s manner was formal and stilted, and the conversation was forced and painful to witness. Confronted with my mother’s determined airs, my father was helpless to relax the atmosphere. I squirmed in my seat and tried to avoid looking at Geraldine. The Sonniers were polite but quiet. After dinner, they excused themselves on some pretext and left, never to return. My mother had made certain to satisfy herself, if no one else, that she was socially alpha.

Growing up, she had learned to play the piano, and on coming of age, she moved to Lafayette to get a bachelor’s degree in music education at the university. That was her ticket to escape the little farming hamlet of Hayes, Louisiana. During her childhood, years of exposure to charismatic revival meetings whose tents periodically popped up in the countryside around Hayes had turned her, not into a fundamentalist, but a sceptic. Surrounded by fire-and-brimstone convictions, her calmly rational mind was a throwback to Enlightenment ideals. Heaven and hell just didn’t make logical sense to her. She claimed to be an agnostic, but I sensed in her a closet atheist. To admit godlessness, however, would have been socially unwise in the midst of Baptists and Methodists in the Louisiana prairies and, in her adult life, surrounded by devout Catholics in the swamplands around Lafayette.

My mother’s scepticism led her to attend, every Sunday, the Unitarian Fellowship in Lafayette, a motley group of about twenty freethinkers, several of them professors at the university. Collectively, they rented a small house and shared the responsibility of giving the service since they couldn’t afford a minister.

Perhaps to maintain the appearance of making sure that her child attended “church,” my mother brought me, scrubbed and overdressed, to the rented house every Sunday morning, while my father stayed home to enjoy the “cathedral of nature” as he called his pastures and cows. At the Fellowship, we were as likely to see a slide show of a microbiologist’s visit to Iceland to study a fungus as we were to hear a meditation on the quest for truth.

My mother was living proof that atheism and Puritanism aren’t necessarily antithetical: the ascetic blood coursing through the veins of her Calvinist ancestors did not mellow out in their otherwise rational descendant, once the carapace of religion had been shed. She was determined to try to curtail any latent vanity in me, so she instructed my father, who had built the family home, not to install a full-length mirror in my bedroom, only a face mirror tucked away inside the closet.

Her need to control and compartmentalize life led her to concoct for me a list of “Morning Routines,” colour-coded “Daily Duties” that only she could decode, and the dreaded “Manners Chart” taped to the wall next to her at the dinner table. If she caught me leaning my elbows on the table, she’d put on her glasses, and with a stubby pencil (neatly tied to a string that was thumb-tacked to the wall) she’d carefully record my demerit as an “X” on the grid. These exercises in discipline and comportment were grim affairs.

Years later, when I was in my late teens, she imparted three moral imperatives: not to drink, not to smoke, and to remain a virgin until marriage. But by the time she got around to informing me, it was too late.

By nature, she was independent and something of a loner. It came as no surprise when she recently told me that she could go for days on end without talking with anyone, and that would be fine with her. As one family acquaintance put it, she was “as taciturn as the day is long.” She took after her father; my main memories of Grandpa were of him grunting an unintelligible greeting when he walked into a room, and watching his favourite television shows from his Lazy-boy: pro-wrestling alternating with evangelical preachers. Silence was his specialty, passed on to my mother by a dominant gene.

Much later, rummaging curiously through the bench of her childhood piano at my grandmother’s house, I discovered a sad little clue from her teen years about her tightly-controlled inner life. On the first page of a boogie-woogie piano score, she had scrawled a self-admonishment not to stray too far from the straight and narrow classical path in music: “I will play this for fun, but I will never take it seriously.”

In contrast to my mother’s cool stoicism and asocial tendencies, my father was gregarious and, most of the time, friendly. Whenever I conjure up his face, he has the proverbial twinkle in his eyes. He always struck me as quintessentially Cajun: loquacious and quick to laugh and “cut jokes.” He came from a large Catholic family of ten children, among whom he had to jostle for attention from his parents. Sensitive and needy, he was, in his marriage to my mother, doomed. In the stalemate following my parents’ frequent clashes, my mother’s favourite punishment was the silent treatment: it came naturally to her, so no expenditure of energy was needed.

The silence nearly drove him mad, as did her fastidiousness and her rage for neatness and order. Once he took her to the swamps in his boat. He would later tell and retell the story of how she complained the whole time about having to pee. Despite my father’s warnings, she had drunk too much water, and she was adamantly not going to soil her white sneakers on the mucky shores of the bayou and squat. He never took her in his boat again.

My father was nothing if not a social animal, and some Saturday mornings he would say to me, “Let’s go veiller,” and we’d visit his parents after stopping by the little country grocery store to buy peppermint sticks for my grandmother and driving through corn fields to arrive at the old Acadian-style home of his childhood. As idyllic as these visits might seem to me in retrospect, childhood is not the age of nostalgia. I was acutely aware that my mother never came along; she was as alien to my Cajun relatives as they were to her. And being the product of the insoluble admixture of my parents’ marriage, belonging to one side or the other did not come naturally to me. I was an observer of the Cajuns just as much as I was the teetotallers.

As warm and fun-loving as my father could be, he never could reconcile himself to the fact that his little girl wasn’t interested in learning about the internal combustion engine of his old Chevy truck or hearing stories of his deep-sea fishing adventures. But I had inherited something of my father’s joking personality, and I used to laugh about the fact that he had tucked into in his wallet a photograph of the enormous Warsaw grouper that he caught in the Gulf of Mexico instead of a picture of me.

Some weekends my father would awaken me at 5:00 to go fishing in the swamps, an activity that we agreed we both enjoyed. I didn’t much care for baiting hooks, but I loved the morbid atmosphere of decay in the semi-tropical jungles with their stagnant bayous, giant cypresses dripping with grey moss, and rotting wooden ruins of old abandoned gas refineries.

Cajun music was anathema to my mother, as trivial as boogie-woogie was in her childhood but distasteful as well. And dancing was out of the question, alien to her body and soul. So to satisfy his love of both, my father would watch the local television programming in Cajun French on Saturday and Sunday mornings. After the intonation of the French rosary by a priest came his favourite show, Passe Partout, whose jovial host, Ambrose Thibodeaux, featured bands with names like “Gaston Cormier and the Mamou Playboys” and “The Bayou Sauvage Ramblers.” Dancers two-stepped, jitterbugged, and waltzed, collectively flowing in a clockwise circle on the dance floor. However vicariously he had to experience his culture, my father watched these shows faithfully, and his need for things Cajun trumped my need for Looney Tunes.

During my childhood, far from being interested in the stubborn fact of my Cajun-ness, I was instead acutely embarrassed by some aspects of the culture, for example, by the “chank-a-chank” music, as it was sometimes pejoratively called, that my father listened to on television. Whenever he turned on his show, I sulked to my bedroom, where I cringed as I heard what I perceived as the nasal wailing of the singers, the choppy accordion din, and the amateurish fiddling that accompanied loping waltzers and the two-steppers who danced as though they had one foot nailed to the floor. I was turning into a teetotaller, I feared, but I couldn’t help myself. I saw Cajun culture as backward and my father as mired in the past. Once, in a rare moment of confiding in me, my mother attributed my father’s disinterest in the “real” culture of literature and classical music to his “lack of a liberal arts education.” But although I was quietly disdainful of his cultural baggage, naturally I never complained about eating my favourite Cajun dishes of crawfish étouffée and gumbo.

Perhaps some of those feelings of condescension had rubbed off on me from the attitude of my mother, or from comments by my maternal grandmother, who used to scour the local newspaper for the police reports and tisk-tisk when she found what she was searching for: Cajuns arrested for drunk driving. Such reports validated her low opinion of that tribe. Or perhaps it was just my own feelings of impatience with what I perceived as the backwardness of small-town and rural life—admittedly itself a kind of narrow-mindedness.

I have since come to appreciate and love many aspects of my father’s patrimoine, and now, relatively late in life, I feel compelled to learn more about Cajun history. However, when I was growing up, that knowledge was hard to come by. As prominent a role as Evangeline played in the culture of my hometown, oddly I have no memory of my teachers talking at any length about the history of the Acadians. And my high school, smack-dab in the heart of Cajun country, offered only one year of French.

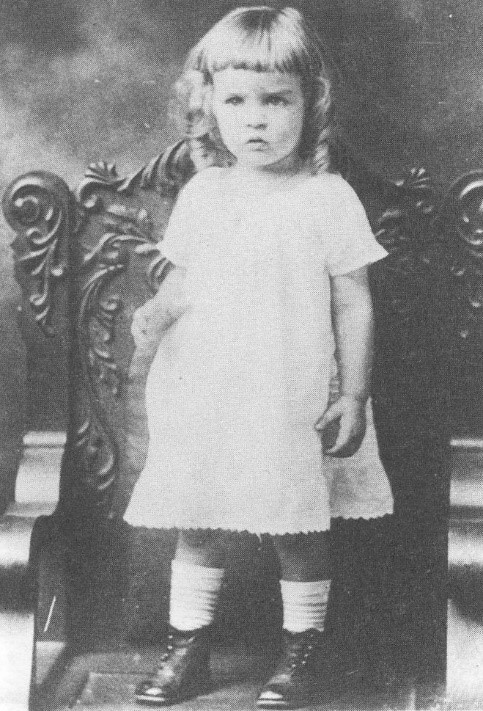

Nor did my relatives talk about the history of the Acadians and their expulsion from Acadie—not, that is, until my father discovered genealogy. On the Christmas of my eleventh year, my mother gave him a present that she had happened upon in an old trunk in the farmhouse of her parents-in-law: a photographic portrait of my father when he was two years old. She framed the portrait and neatly wrapped it in Christmas paper and ribbons.

My father opened it and we stared at the image. Puzzled, I asked who it was, and my mother announced, almost triumphantly it seemed to me, “It’s Daddy!” Anyone would have taken him for a little girl: blondish shoulder-length hair styled in ringlets rivalling those of Shirley Temple, bangs cut straight across his forehead, and a cute little white smock hemmed with eyelet lace. Such was the conventional unisex garb for toddlers of the 1920s, and it was a rite of passage for little boys to graduate to their first pair of trousers.

My father quietly accepted my mother’s present, but it seemed obvious to me that he felt humiliated. Knowing my mother’s ways, I thought of the gift as emasculating. I remembered seeing that look on my father’s face twice before. The first time was when my mother decided that I would help her to put a fresh coat of paint on his old red pickup truck while he was away for a couple of days. If it weren’t bad enough that our brush strokes were plainly visible, she had the brilliant idea to stick little decals of birds and butterflies on the exterior of the truck’s cab. She had enlisted me for that job, which delighted me but simultaneously filled me with a vague sense of unease. When he got home, she showed him his “present.” He took one look at it and without saying a word, stalked into the house. A few minutes later, he emerged grim-faced to embark on a long fishing trip in the swamps—in his white station wagon.

The second time was when my mother grew weary of being the wife of a man who raised cattle and chickens as an avocation to carry on the farming tradition of his parents. She couldn’t persuade him to get rid of the cows, so she insisted on dispensing with the rooster, Mister, and his harem of chickens—in spite of the free eggs. Again, she recruited me to help her, and together we chased the panicked birds and shoved them, flapping and squawking, into wooden crates. She drove them away, and I never found out what she did with them. My father was nowhere in sight. He had escaped to the swamps in advance of her pillage.

In light of his reaction to the gift of the girlish portrait, I was surprised to learn that that image was the catalyst for his interest in genealogy. Over the years, and especially during his retirement, genealogy became an obsession. He persuaded my mother to help him, and together they logged countless hours searching in old, obscure parish records and nooks and crannies of relatives’ attics to find every possible shred of evidence to document ancestral existence, from wills to portraits to cattle brands. My mother had an eye for detail and a penchant for accuracy, and the work had its appeal for her. My father took hundreds of photographs of ancestors’ likenesses and developed them in a dark room he had fashioned in a small barn. He framed and displayed many of them throughout the house along with the cattle brands and other antique farming tools. Our house soon resembled the headquarters of the Lafayette Historical Society, and the shelves of his home office were stacked high with yellow boxes of slide carousels filled with the spoils of his research.

His slide projector, loaded with those carousels, was the primary instrument of my torture during adolescence. Many an afternoon, no sooner would I come home from school than he would summon me to the darkened family room and project onto a screen an interminable stream of hoary old ancestors. For me, these pedagogical sessions were as tedious as learning about pistons and carburetors. Since I couldn’t escape to the swamps like he did when he fled from my mother’s eccentricities, I simply blanked out during the roll-call of saints in his ancestor worship. Dupuis, Guidry, Boudreaux, Prejean: these surnames had no meaning for me unless attached to a known living person. To my chagrin, I once saw him holding his four-year-old grand-nephew in his arms, earnestly endeavouring to teach him the names of ancestors and their relationships from a detailed family tree taped to a wall. But perhaps most of all, I resented being usurped from my father’s attention by a host of sour-looking progenitors.

The word “posterity” became a joke in my family: everything, it seemed, was being salvaged for the edification of future generations. Soon it wasn’t only the artefacts of the dead but also those of the living—letters and other memorabilia—that were in danger of becoming fodder for the life eternal of historic preservation and ending up under glass museum cases even while we still breathed. Life, it seemed, was a dress rehearsal for posterity.

And attaining immortality, we Martins and our cousins to the seventh power—living and dead—were gathered in the thick tome that my father felt to be his greatest achievement in life: his genealogy of the Martins entitled Remember Us. Referred to in the family (usually with an eyeroll) as “the Martin Bible,” it contained meticulously researched charts of ancestors and their begettings, as well as exhaustive documentation of portraits and wills carefully copied and preserved over the years. The cattle brands were there, too, assigned to their proper owners.

Genealogy for my father represented the safeguarding of a traditional culture that was slipping away—for him, personally, and for the larger Cajun community—as the gradual assimilation into mainstream American culture took its toll. And Evangeline represented the ultimate prize in his genealogical salvage operation. He came to believe fervently that the Martins had the privilege of being linked by blood to an actual historical Evangeline. For him, this association was even more prestigious than being related to King Gabriel of the 1928 Mardi Gras. I was now the distant cousin of a myth.

The belief of my father (and many other Cajuns) in the historical reality of a flesh-and-bones Evangeline is the poignant result of her transformation from Longfellow’s tragic literary heroine into an actual Acadian woman who lived through the 1755 British expulsion of the Acadians—and who could have conceivably been pinpointed on some lucky family tree. According to Longfellow’s version of the tragedy: before Evangeline Bellefontaine and Gabriel Lajeunesse are able to marry, the British herd the lovers into separate ships. Evangeline’s prolonged and fruitless search for Gabriel finally ends when she, now an elderly nun, miraculously finds him dying in a Philadelphia hospital. Shortly after their reunion, Gabriel expires and—get out your handkerchiefs—so does Evangeline.

I can attest to the power that Evangeline held on some Cajuns’ need to believe that their beloved symbol of diasporic suffering was more than just a legend, more than the protagonist handed to the Cajuns on a literary platter by Longfellow. My father used to impress upon me that Evangeline was, in reality, an orphan named Emmeline Labiche, adopted by one of our ancestors in the now-dim Acadian past. My father derived this information from a work of historical fiction (which he and many other Cajuns took as factual reportage) by one Felix Voorhies, a writer of Dutch-Cajun heritage. Voorhies frames his novella using the common authorial ruse of claiming that the story about to be told is in fact a chronicle of historical events and persons. Countless other authors have used the same subterfuge, either to make the work of fiction more palatable to readers who considered the consumption of fiction to be morally questionable, or to give the work an air of authenticity. I’m guessing that the latter motivated Voorhies to claim that his grandmother was told by her grandmother, and so on, the story of Emmeline Labiche, the real Evangeline, which he now passes along in his little book to all who wish to render incarnate the virginal symbol of Cajun identity.

How Catholic, in a way: Evangeline was now a perpetual virgin fit to worship, and worship her the Cajuns did, at her statue situated on the grounds of the historic St. Martin de Tours Church in St. Martinsville, Louisiana.

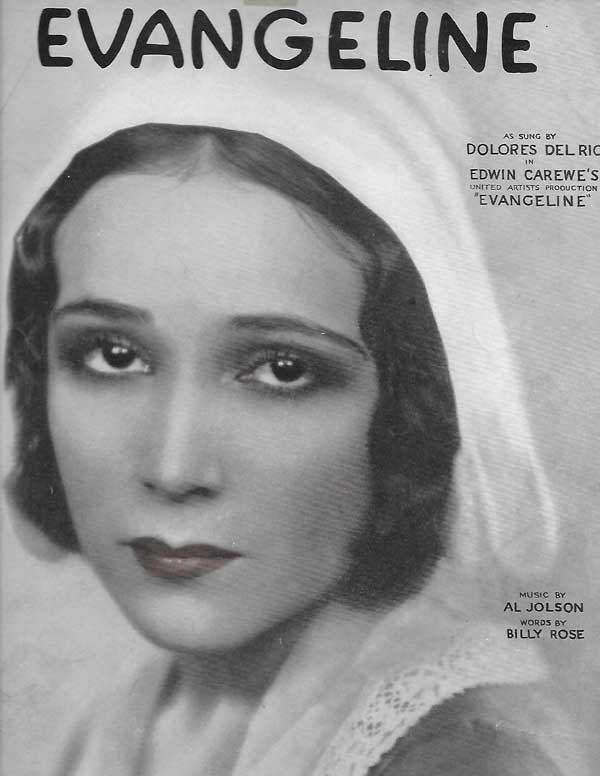

But like Voorhies’ novella, the statue was also a product of fictional representation: it was modeled in the image of Delores Del Rio, the Mexican-American actress who played the romantic lead in the 1927 film Evangeline.

When I was growing up, the statue was believed by some to be a likeness of an historical Acadian woman and not the star of a silent film.

And because the statue is situated near a live oak tree next to St. Martin de Tours Church, it becomes all the more believable that the historical Evangeline must be buried there. After all, in Voorhies’ account she was buried under a live oak tree soon after becoming mentally unhinged, Ophelia-like, on arriving in St. Martinsville only to discover that Gabriel had given up hope of her arrival and married someone else. Naturally, the more that real accoutrements like a statue, an oak tree, and a book attach to a myth, the more credible the tale becomes.

And the narrative of Evangeline is extraordinarily malleable, ideal for appropriation to reaffirm whatever the values of a community or individual, such as class hierarchy, as in Queen Evangeline of Lafayette’s Mardi Gras. Like the Virgin Mary, Evangeline’s iconic status can bestow blessings on anything from preserving cultural heritage to selling eyeglasses. Evangeline Maid Bread tries to have it both ways: it puns on the virginal “maiden” of legend while depicting her as a slender Betty Crocker-like icon in a French maid’s outfit designed to appeal to Cajun housewives of the 50s and 60s.

As much as Evangeline has become a symbol for the Cajun homeland, ironically the fictional character never truly arrives home. Expelled from Acadie with thousands of others, she makes her way to Louisiana, but her arrival is anything but a homecoming. In both the Longfellow and Voorhies versions, Evangeline/Emmeline is a perpetual wanderer, lost in the wilderness looking for Gabriel or else lost in the wilderness of her insanity. Perhaps, in a way, I came to identify with her because of her unrootedness. It wasn’t a lost love or insanity that alienated me from home, but observation of difference brought on by a split allegiance between mother and father, teetotallers and freewheelers.

My father died two years ago. He had been in a nursing home in Lafayette trying to recover from a stroke that left him almost completely unable to speak or walk. I immediately flew from Toronto, now my home for the past four years, to help care for him. He tried valiantly but the damage was too great. I had come to see him as an icon of the Cajun culture, a dying way of life that he held on to by documenting it. A couple of weeks before he died, I was in his hospital room with my mother, who had encouraged me to read a poem to him that I had recently published, about trying unsuccessfully to find home. I don’t think that I knew what it was really about until I started to read it to him.

Around the same time, my mother was diagnosed with the onset of Alzheimer’s. In my weekly telephone conversations with her, I know that before long she will not know who I am, so I try to get her to talk about the past: she doesn’t always know where she is, but the price she paid for roller skates in the 1930s still readily surfaces to consciousness. Although her quirkiness still has the power to annoy me, she is easier to get along with now. The rigidity has loosened, and the moralizing has vanished. She even laughed when I told her the “testicles” story.

Last summer, I made “the pilgrimage,” as my Cajun relatives call it, to Nova Scotia. I had the idea to write a poetic sequence based on my heritage. During my trip, Evangeline kept reasserting her presence as a kind of tutelary spirit. It wasn’t just the fact that her name and image were as almost as prevalent in French Nova Scotia as they were in Louisiana. There was something about her that represented to me, on the one hand, the love of home and traditional ways, and on the other, my scepticism about myths and their tendency to smooth over the unruly layers of history and become all things to all people. It was as though I were looking at Evangeline through the eyes of both parents.

One of the high points of my travels was my participation in an archaeological dig at the historic site of the Acadian village of Beaubassin. I had brought Remember Us with me, so I knew from my father’s research that many of my ancestors had lived in that village before their expulsion in 1755. As I knelt in the square pit to which I had been assigned, I began scraping away layers of the past, two centimetres at a time. Under my trowel emerged an iridescent piece of curved glass—possibly from a wine bottle, the archaeologist informed me—and a reddish piece of pottery—which he speculated might evidence trade between the Acadians and the Québéecois. As I unearthed several fragments of white clay smoking pipes, I felt a frisson imagining my direct ancestors smoking the very pipes that I was now retrieving from their slumber of two-and-a-half centuries.

The archaeologist told me that many people whose ancestors had lived in Beaubassin have participated in the dig, and that some are moved to tears. I tried on that emotion for size as I reminded myself solemnly that my ancestors were among more than two thousand Acadians who had been deported from this village alone. But the sentiment just didn’t fit. Now, as in my childhood, I felt myself to be an observer. I still wasn’t home, but I was content not to feel the pangs of having lost an imagined arcadian past.

Evangeline’s meaning for me is a double-edged sword. Her person and story, in all its guises, is powerfully associated with my emotional attachment to home and to the Acadian culture. She conjures deeply engrained and involuntary feelings of nostalgia. But I’m also interested in Evangeline as the creation of a people whose desire to keep the tribe together breathed historical life into a literary character and endowed her with symbolic meaning.

“Acadie exists in the real and the imaginary defeats it”: my epigraph by New Brunswick poet Gérald LeBlanc suggests by extension that the story of Evangeline is a dance between the real and the imaginary. The real—the mundane events of life—continually comes into being and is vanquished the moment we perceive it, remember it, and create a story about it. Forever after, we remember a memory of it. My own act of recovering something of my past also involves a recreation, an ordering, an interpretation, just as Cajuns have done with Evangeline. Perhaps home is so elusive because from the outset, memory is memorial. It is also my daily bread.